Modules

Close Python interpreter and enter it again, the definitions you have made (functions and variables) are lost.That leads us to writing our code in a file and passing it to the Python interpreter as an input. AKA creating/writing a script.

- Module: Python codes written in a file.

- Anything written in a Python file can be imported into another module.

- So when our program growth, we can split it into several files for:

- Easier maintenance.

- Reusability: a function is defined in one file and can be used in several programs.

import turtle

turtle.pendown()

turtle.speed("fast")

def square(length: int) -> None:

"""Draw a square"""

for side in range(0, 4):

turtle.forward(length)

turtle.right(90)

def diamond(length: int) -> None:

"""Draw a diamond"""

turtle.left(45)

turtle.forward(length / 1.4)

for _ in range(3):

turtle.right(90)

turtle.forward(length * 1.4)

turtle.right(90)

turtle.forward(length / 1.4)

def shape1():

for _ in range(72):

square(100)

turtle.left(5)

def enclosed_square_with_diamond(length: int) -> None:

square(length)

diamond(length)

enclosed_square_with_diamond(100)

# shape1()

turtle.done()

Virtually everything that your Python program creates or acts on is an object. But the question is how does Python keep track of all these names so that they don’t interfere with one another?

Scopes

- Classes, functions & modules create scope.

- Where something exists.

- Where we can use an object.

Namespace

- The structures used to organize the symbolic names assigned to objects.

- Think of them as baskets with different things in it. You can have two pair of black socks in different baskets without interfering with each other, right?

[!NOTE]

dirfunction:

- Returns a list of objects inside the module passed to it.

import math print(dir(math))- When invoked without any argument it will return a list of current local scope’s objects.

def sum(num1: int, num2: int) -> int: result = num1 + num2 print(dir()) return result sum(1, 13)- The names starting and ending with double underscore is what commonly is known as “dunder”. We usually ain’t interested in them.

globalsfunction:

- Returns a dictionary.

- It contains all the globally scoped names.

- Basically same as

dir(), but:

- Will just return the current module’s global names.

- You can see the value of each name.

print(globals())

localsfunction:

- Returns a dictionary.

- Variables inside that function + their values.

def abc(distance: float, /, *, name: str): print(locals()) abc(45.23, name="Tokyo")

Pop Quiz

| Code | Where is it available? | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ```py import turtle def square(length: int) -> None: """Draw a square""" for side in range(0, 4): turtle.forward(length) turtle.right(90) ``` |

|

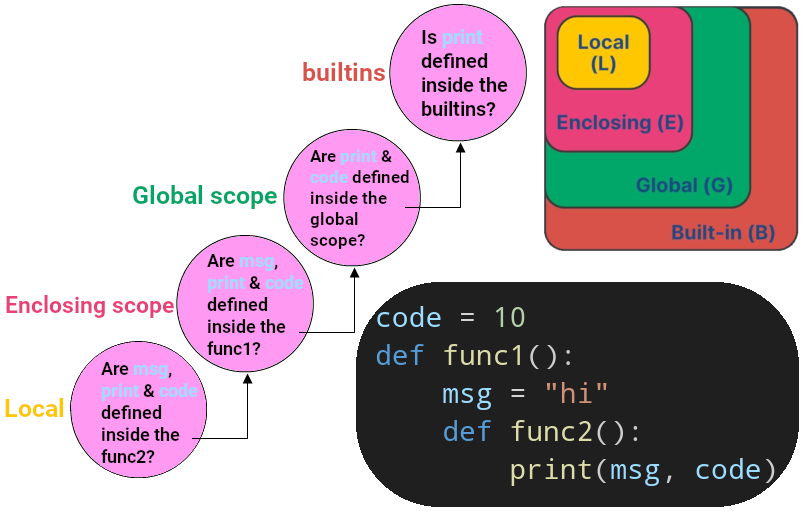

How Python Look For a Variable?

- If Python doesn’t find a name in the local namespace, it searches the global namespace next.

- If it doesn’t find the name in there either, it searches the

builtinsnamespace. - If the name is found in the

builtinsnamespace, Python can get the object to use. - If still it was unable to find the variable it will crashes with a

NameErrorexception.

[!NOTE]

You can see a list of built-in functions and variables like this:

import builtins print(dir(builtins)) # Or alternatively: print(dir(__builtins__))You might think this is pretty inefficient. Just think about it, how much lookup Python has to do each time to find a variable. That’s why we have free variables in Python.

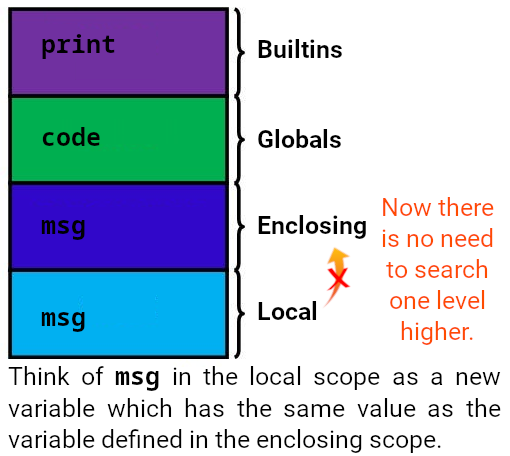

Basically a free variable is one that is being used in an scope but ain’t defined there. Like

msg.

Important notes about free variables:

- Global variables won’t become a free variable.

- Check the performance improvements section.

Lifetime of Different Namespaces

Python Creates new namespaces whenever it is necessary and deletes them when they’re no longer needed:

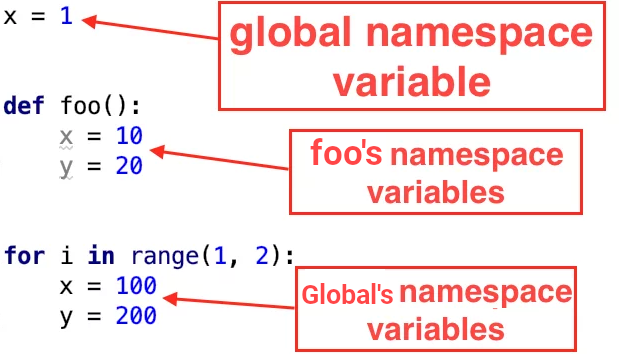

| Builtins | Global | Enclosing | Local | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | As long as Python is running. | Any names defined at the level of the main program. | Local to the function. | Just inside the function/class. |

| Created | When Python starts up. | When the main program body starts. | Whenever a function executes. | When we’ve defined a function inside another function. |

| Deleted | When Python interpreter is terminated. | When Python interpreter is terminated. | When Python terminates function execution. | on function execution termination. |

[!NOTE]

Each module has its own global namespace too!

[!CAUTION]

When you wanna change the value of a variable defined in the enclosing scope you need to use

nonlocalorglobalkeywords (keep in mind that this is not a good idea since your functions should be pure):

What is happening here what we know commonly as _name shadowing_. All this means is that we've used same variable name in the inner circle. buggy.pyfixed-but-horrible-code.pyfixed-and-better.py```py code = 10 def func1() -> None: temp = 1 def func2() -> None: # Python creates a new, completely independent variable! temp = 12 # Python creates a new, completely independent variable! code = temp * 10 print("Inside func2 temp is:", temp, "\tand its id is:", id(temp)) func2() print('-' * 80) print("Inside func1 temp is:", temp, "\tand its id is:", id(temp)) func1() ``` ```py code = 10 def func1() -> None: temp = 1 def func2() -> None: nonlocal temp global code temp = 12 code = temp * 10 print("Inside func2 temp is:", temp, "\tand its id is:", id(temp)) func2() print('-' * 80) print("Inside func1 temp is:", temp, "\tand its id is:", id(temp)) func1() ``` ```py code = 10 def func1() -> int: temp = 1 def func2() -> tuple[int, int]: """The first index of tuple is temp and the second is code""" temp = 12 code = temp * 10 return (temp, code) (temp, code) = func2() print(temp) return code code = func1() print(code) ```

Scopes and namespaces example

```py def scope_test(): def do_local(): spam = "local spam" def do_nonlocal(): nonlocal spam spam = "nonlocal spam" def do_global(): global spam spam = "global spam" spam = "test spam" do_local() print("After local assignment:", spam) do_nonlocal() print("After nonlocal assignment:", spam) do_global() print("After global assignment:", spam) scope_test() print("In global scope:", spam) ```

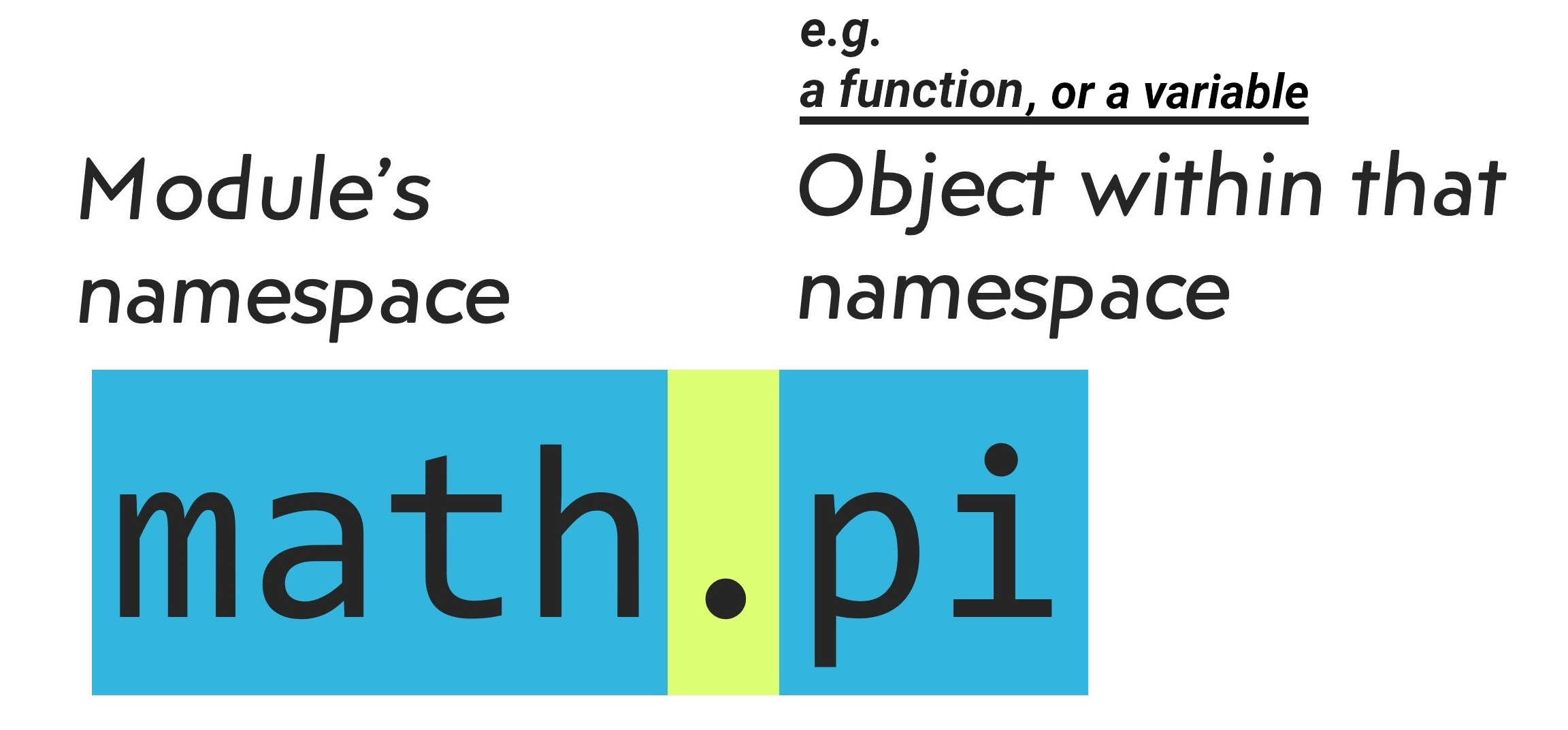

Each Module Has Its Own Namespace

In an imported module we can access objects within it by using this namespace thingy. So we know each module has its own private namespace:

[!NOTE]

Event though we say it is private, but you should keep in mind it is not private in the traditional sense that you cannot access it from outside of a module. In fact we have access to all objects defined inside a module in Python.

It is customary to place all import statements at the beginning of a module.

import math

import typings

# more imports

# Rest of the code

[!TIP]

You can import inside another function:

def func() -> None: import math print(math.pi)

There is a variation of import that will only pull in a specific object:

def func() -> list[int]:

hi()

return [1, 2, 3]

[!TIP]

# You can even import every objects that a module has like this:

from math import * print(pi)

- Do NOT use it since it might collide with other names.

- It is considered anti-pattern (ref).

- OK when you’re in REPL and just wanna test something.

One other thing is renaming the import, so that we have a different name bounded to a module, this is particularly useful when you wanna import something but in where you need to import it you have another object with the same name:

from math import pi as BUILTIN_PI

PI = 3.14

[!TIP]

In PEP 8 the convention for naming constants is to use all uppercase letter and separate words with underscore.

Creating Our First Module

main.py | greet.py |

|---|---|

| ```py import greet # from greet import in_japanese # Katakana of Mohammad name = "モハマド" # message = in_japanese(name) message = greet.in_japanese(name) print(message) ``` |

```py

"""A greeting module in different languages"""

print(" |

[!TIP]

- Codes written outside functions or classes will be executed right away when Python encounters the first time you’ve imported that module somewhere. Learn more in the caching section.

- The first line can be docstring for the module, you can access it via dunder

__doc__.

Caching Modules

- Python caches every module only for the first time.

- In other word Python do not recompile a module several times.

- Python stores the compiled module in its cache

- In the future when we import the same module it immediately return the previously imported module.

- Caches are stored in the

__pycache__directory.

[!TIP]

But we can tell python to reload a module too:

import b import importlib importlib.reload(b)

- Cache invalidation:

- Python checks the modification date of the source.

- Against the compiled version to see if it’s out of date and needs to be recompiled.

- A completely automatic process.

[!TIP]

You might think with yourself which one is better, pulling in all the names exported from a module or just the things I need? In other words,

import mathVSfrom math import pow. So here are things you might wanna take into account when deciding to do what:

- Python in both situation will go through the code top to bottom the very first time you’ve imported something and creates a compiled version of it for faster loading in subsequent imports.

- You might use

from math import pi as PIfor the sake of ease of use.- Or you might wanna keep your code readable and not polluting the global namespace, then

import mathis the way to go.- It worth noting that with

import mathand then using it like this:math.pow(2, 2)means that Python before executing thepowfunction has to perform 2 lookups, first it needs to findmathvariable in the global scope and thenpowmethod inside that module.

__name__

- It is the module name.

- It’s gonna be

__main__if you call the python interpreter with that file as its input.

[!TIP]

Making

greet.pyboth executable as a script and importable we can add the following code to it:import sys if __name__ == "__main__": print(in_japanese(sys.argv[1:][0]))And now you can run a command like this in your terminal:

python greet.py ジャワド

- A convenient user interface to a module.

- Can be useful when testing something.

- Example: Electron project.

The Module Search Path

This is how Python finds and loads modules it look for it in this specific order:

- Searches for a built-in module with that name.

import sys print(sys.builtin_module_names) - Not found? Python searches for the file name

.pyin:- The location you’ve executed your python script.

- Directories in

PYTHONPATH(initialized fromsys.path). - Python’s default installation paths.

Why This Matters?

- Create a file named

sys.py:some = 123 - Create another file named

main.py:import sys print(sys.some)

But the same is not correct about math, though the intellisense will be annoying.

Python Library Reference

- A library of standard modules.

- Not part of the core of the language.

-

Platform dependent:

Some Boosting Performance Techniques – Change Your Mindset

There is a technique that you might see in codebases used to improve performance, leveraging the concept of free variables. E.g. in our square function we can do something like this:

def square(length: int) -> None:

"""Draw a square"""

inner_forward = turtle.forward

inner_right = turtle.right

for side in range(0, 4):

inner_forward(length)

inner_right(90)

This might improve the performance measurably if we had a bigger loop (a million times), but even in that scenario you must first try to improve other parts of your app first and this is more like “last resort” solution.

[!TIP]

When trying to improve performance think of:

- What your code is doing?

- What is causing it slow down?

E.g. in our turtle app it is obvious that our code is interacting with the screen and telling it to draw what with every change. So if we could just shutdown that part of our app and get the final result when Python has calculated the final image would give us the performance we wanted to have.

turtle.Screen().tracer(0) # Disabling turtle animations

# and when you need to see the outcome of your code you can:

turtle.Screen().update()

[!NOTE]

If you use

turtle.done()you do not need to callturtle.Screen().update()since it will does the updating for you on top of preventing the window from being closed.